Datafication, algorithms and AI are shaping how we live, reside, and work – and profoundly affect power relations in the city. As part of the Cities for Change team, CN worked with the concept of digital courage: the courage of cities to choose and invest in technologies that benefit their citizens and communities in the long term. The ‘Digital Courage’ project was an exploration of the influence of digital infrastructure and the platform economy on the city. What is the damage and how can it be different? We investigated how we can challenge the current dynamics and move from the reign of the hyper-individual user and big tech dominance towards collective solidarity.

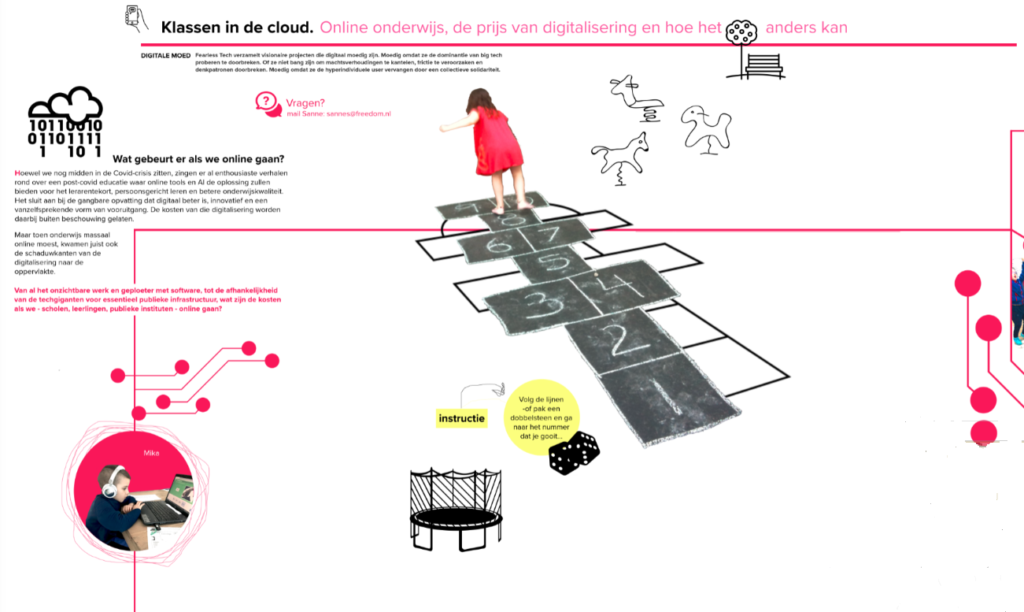

Our collaborator, researcher and activist Sanne Stevens who is a fellow at LSE, led the research and curated a digital exposition. The expo shows the shadow sides of the digital transformation, and how these disproportionately impact certain often more vulnerable, communities over others. The research zoomed in on delivery workers and primary education teachers, and how digital transformation has been affecting them. Specifically, an Uber Eats driver and a primary school teacher using technology to teach her students online during the pandemic.

Optimising for convenience comes with a price

The research and expo show how in the delivery sector platform companies prey on the weaker groups in society, primarily immigrants and other vulnerable groups. An Uber Eats driver for example often makes less than minimum wage, has little rights and is in constant competition with his or her colleagues. Teaching with Microsoft and Google classroom creates inequality between students, but also privatizes our public infrastructures. Effectively we end up with the situation that big tech designs our education systems. Is this desirable?

More generally, taken along by the neoliberal ethics of productivity and efficiency we are letting convenience lure us into the use of certain tools. Digital tools are being optimised for convenience, not for democratic governance or privacy for example.

‘’Accelerated by he Covid-19 Pandemic Microsoft and Google have wrestled their way into educational systems. We see a large transfer from collective public infrastructure to largely private infrastructures.’’ Paul Keller – Open Future

This transition is also playing out in the cultural sector, Facebook / Meta has positioned itself as intermediaries between public institutions and their audiences. This intermediation function weakens cultural institutions, cuts them off from direct access to sector. But we have to pose the question: ‘How do we reach our audiences’? and more importantly ‘How would we like to reach our audiences?’

The dominant narrative of digital capitalism centred around efficiency holds that the commercial platform, now mainstream solutions work really well. However, we should ask ourselves the question, do they really do work so well? What are we optimising for? What do we value?

These tools make the world look simple even though it’s not, they hide complexity, thrive on quantification and ‘babyfy’ users. Indeed the implications of a certain tool for privacy, collective wellbeing, equality and democracy are often not clear to the individual user and also probably should not be their responsibility.

’Big parts of Society are not knowledgeable of what trade offs they actually make.‘’ Sander de Waal – Waag

Another frame of mind- Technology to the rescue

We can move to another frame of mind: let the norm be defined by the system that we want. We can co-design with communities and create the technologies that people need, instead of mimicking functionalities we do not actually need. In public infrastructures, technologies should be public-interest based.

Technology can be used to serve equity, solidarity and needs of community through for example civic crowdfunding, and mixing social entrepreneurship and social innovation with solidarity and activism. There is a big role for public institutions in supporting and investing in alternatives, and we see growing awareness there.

How to resist, how to create alternatives –the main lines of action:

- Massive public investment into community friendly and needs-based public technologies and infrastructures.

- Regulation, imposing norms. Such as the Digital Markets Act and Digital Services Act on a European level.

- Countering the dominant narrative of convenience and efficiency of digital capitalism. It’s not working well, it’s just hiding complexity. We should optimize for things people and the collective actually need.

- Involving citizens and communities in design: design justice, needs based.

- Interoperability – demand and stimulate open standards and cooperation

- Classic political actions: organising. Politicise what is happening: unions, pushing back from the daily lives of people being affected.

The research and public events allowed for exchange with a range of experts and communities, including Sedah Gürses of Delft University, Meliani Touriani- Councillor of Digital Affairs Amsterdam Municipality, Aik van Eeemeren, CTO office Amsterdam Municipality.

A conversation with Geert Jan Boogaerts of Public Spaces/VPRO, Oliver Schulbaum of Platoniq in Spain, Paul Keller of Open Future, en Sander de Waal of Waag.

The project started in January 2020 and ran until June 2021 and was done in collaboration with the 99ofAmsterdam- the City of Amsterdam Fearless Project.

Two expos that were created during the project:

☰

☰